Running this site for the last year and a half has exposed us to a whole world of legal issues that appear to be little known in the architecture community. We started this project because it was hard to find images of authentic, diverse people, doing the kind of everyday (and sometimes not-so-everyday) things that renderings require. As a result, we took a guerrilla approach to finding and cutting out images, and have always been up front about the fact that we don't have the rights to most of the images on the site. As it turns out, even we weren't aware of all of the legal facets of using cutout figures in architectural rendering.

Before we go any further, it's important to put in a little legal disclaimer, because that's the kind of world we live in: this is not legal advice, in the strict sense of that term. This is based on personal research (here's one good site to check out), and off-the-record conversations with legal professionals. In other words, this is what we believe, but you should consult your own lawyer before using anything off of this site. Got it? Good, read on.

Basically there are two things you need to be aware of when using images found online. The first, and most obvious, is copyright. Whoever took that photo owns the rights to it. Period. In most cases they don't even have to register it, the copyright is implicit. Accordingly, if you use that image - or a portion of that image - without their permission, you're violating the law. Now, fair use laws outline a number of uses in which it's actually okay to violate their copyright. These are a bit ambiguous, but generally educational and strictly non-commercial uses fall under fair use. So, if you're cutting out images to use on a school project, you're probably within operating with fair use and don't need to worry about the copyright. If you're a firm using these images for your own work, or for competitions, or really anything where you're trying to get paid you most certainly do need to worry about the copyright.

This is one of the big red flags we've come across regarding rendering practices in the field of architecture: renderings are almost always considered commercial use. They are a form of advertising. Whether you're showing them to a client, using them for a competition, putting them on your website, or getting them published on Dezeen, they are almost certainly going to be ruled commercial or advertising use, which means you are operating outside of fair use and subject to the strictest interpretation of copyright laws. Unfortunately for all of us, they aren't legally considered art, and don't get special treatment.

So what's to stop us from going out and taking our own photographs of people on the street, cutting those out, and using them in our renderings or on this site? That's where the right to someone's likeness comes in, or "right to publicity" depending on the state. Basically, each of us has a certain degree of ownership over our own likeness. There are certain exceptions, and you give up certain rights by going out in public. For instance, in most cases, if you take a photo of someone on the street, you can legally sell that image as a portrait. You can also sell almost any image taken in a public space for "editorial use", which usually means to a newspaper or magazine for specific journalistic purposes. This is again where fair use comes in, and our understanding is that someone's likeness can be used without explicit permission if it is for educational, non-commercial use.

But what you can't do under any circumstances, is use someone's likeness for "commercial" or advertising purposes without their consent. This is what keeps Coca-Cola from using images of people drinking Coke on the street in their ad campaigns. Instead, they have to pay models large sums of money for the privilege of using their likeness.

As outlined above, this is what architects should be doing also. Using someone's likeness to promote design services is very much a commercial use. This means that even if you receive permission from the copyright owner of an image (or you own the copyright yourself), you still need the person featured to sign a model release granting you permission to use their likeness in a commercial context.

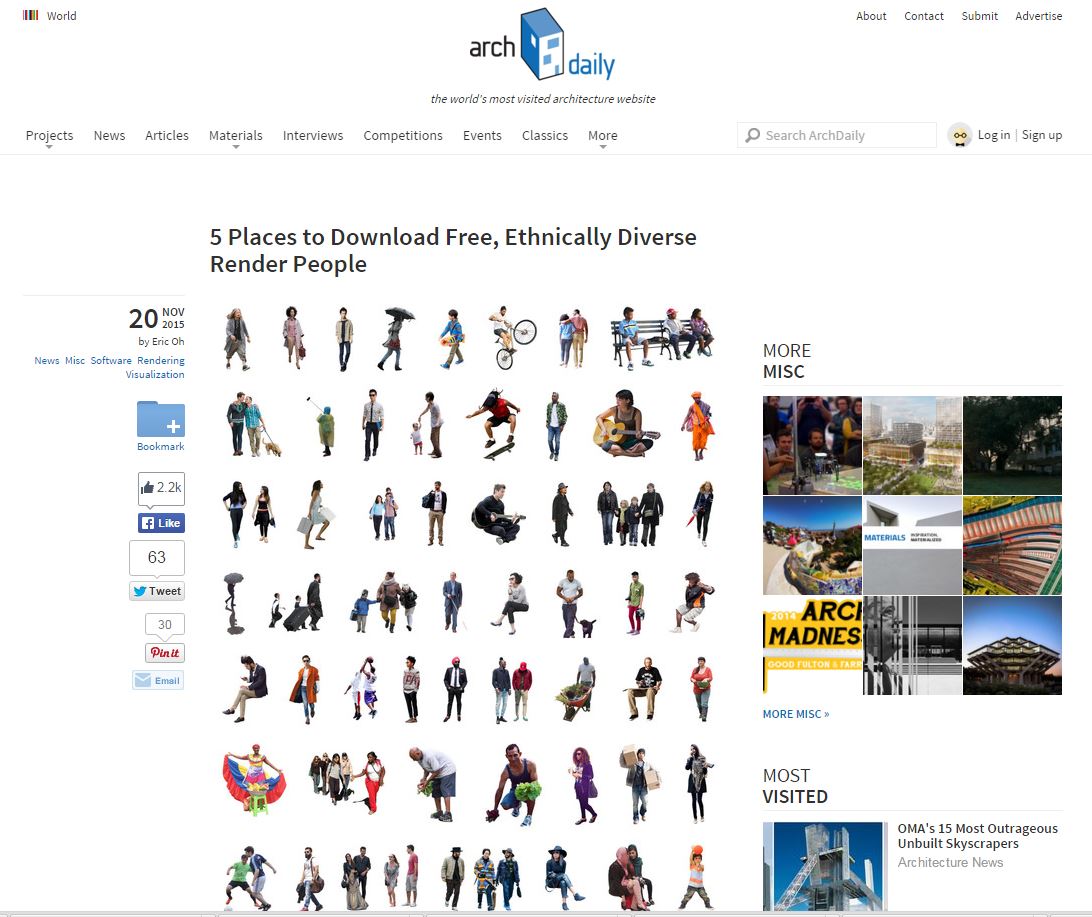

If this all seems like a lot of new information, it's because few people in the architectural community seem to be aware of these regulations, and the vast majority of cutout sites either don't have own the copyright, don't have model releases, or both. That's a pretty big deal given the extent to which even large architecture firms tend to get their cutout figures from these sites. There's not a lot of precedent for this kind of lawsuit in architecture, but given the money involved in the design and construction of a building, even minor damages could amount to a very large sum.

So, what should you do? First, if you can afford it, check with a legal professional. Second, figure out where your cutouts are coming from and make sure you're getting permission to use both the copyright and the likeness in the image. If you're not, find a better resource, or get comfortable with the legal risk.

Okay, now for our bit. What have we done? We don't want to take these images offline. There's a clear need for increased diversity in architectural representation, and we want to help people achieve that in their renderings, and engage with those issues in a deeper way. But we also want to provide an options for non-students. As such, we've reorganized around three galleries featuring modified versions of the same images:

- "Cutouts" - this is our new landing page, and our working title for the style. These are images that have been stylized in such a way that we've rendered the individual unidentifiable, while still preserving a distinct aesthetic. This gets us around the issue of likeness, and puts us squarely into the legal grey area of whether this constitutes enough modification of the original image to be considered fair use. Our position is that it does, which would make it legal for commercial use. You should, however, make your own judgment before using these images (unfortunately the Shepard Fairey case doesn't shed a whole lot of light on the issue).

- "Silhouettes" - these are straightforward, and even more clear cut than the previous category. We believe these are well within fair use laws, and should be usable in all commercial work.

- "Originals" - and so, finally, we arrive back at our original images. These are still available, but tucked away behind an additional level of acknowledgment that they are intended for educational and otherwise non-commercial use only. Use very much at your own risk.

We've also taken down the "submit" and "tags" pages, for reasons that we'll go into in another post. For now, let us know what you think about the change at nonscandinavia@gmail.com.